CS173: Intro to Computer Science - Introduction to Cryptography

Activity Goals

The goals of this activity are:- To relate the mathematics of modern encryption systems to applied principles of information hiding

The Activity

Directions

Consider the activity models and answer the questions provided. First reflect on these questions on your own briefly, before discussing and comparing your thoughts with your group. Appoint one member of your group to discuss your findings with the class, and the rest of the group should help that member prepare their response. Answer each question individually from the activity, and compare with your group to prepare for our whole-class discussion. After class, think about the questions in the reflective prompt and respond to those individually in your notebook. Report out on areas of disagreement or items for which you and your group identified alternative approaches. Write down and report out questions you encountered along the way for group discussion.Model 1: An Unplugged Activity

Questions

- Try sending a message to a classmate using the Vertex Cover Problem.

- How might you decrypt this message? What information would you need to know? This is the secret that makes up the private map, and it is the solution to the Vertex Cover Problem.

- This method works to encrypt and decrypt numbers. How can we use this model to send text messages?

- What prevents just anyone from solving the Vertex Cover Problem and decrypting your messages?

- Make your own private map and corresponding public map. Give your partner your public map, and encrypt a value on each other's maps. Try decrypting it on your private map!

Model 2: The RSA Cryptosystem

Questions

- Generate an RSA key and try it out with a message of your own by encrypting one character at a time!

- How is iteration useful when encrypting messages with a public key?

This activity is adapted from Prof. Mongan’s assignments in communications and introductory cryptography [1, 2, 3], from the CS Unplugged Public Key Encryption lesson module [4], and Dr. Jeffrey Popyack’s online RSA Calculator [5].

Background: Sending Secrets

If you had to pass secret messages around the room, but had to do so by passing notes to the people immediately adjacent to you, how could you go about “securing” the messages so that only your partner at the other side of the room could read your note? You and your partner would have to agree on some encoding for the message. Many such encodings exist:

One limitation is that you and your partner must agree upon the details of the encoding. But how do you exchange that information? You’d have to pass it through your neighbors again, and thus would not be a secret. Public Key Cryptography provides us with mechanisms by which we can generate a key (a basis for an encoding), and make just enough information about it publicly available that others can use it to secure messages to us. Everyone gets to see this information - it’s enough to encrypt a message, but, amazingly, it’s not enough to decrypt it! Often, these cryptosystems are used to generate and send symmetric keys like the ones above, and this is the subject of secure Key Exchange algorithms.

Securing Data with Asymmetic Key Cryptosystems Using a Harde-to-Solve Problem

We need a scheme whereby the sender can know something public - everyone can know it! Knowing the public part tells you nothing about how to decode a message, but actually allows you to encode the message for the recipient to secretly decode. The secret is never shared, so it is never transmitted. How can we do this? The idea is to generate a piece of information that contains the mechanism for encryption and decryption, but in such a way that it is very difficult to extract that mechanism - this is akin to extracting the original ingredients from a stew.

The Vertex Cover Problem

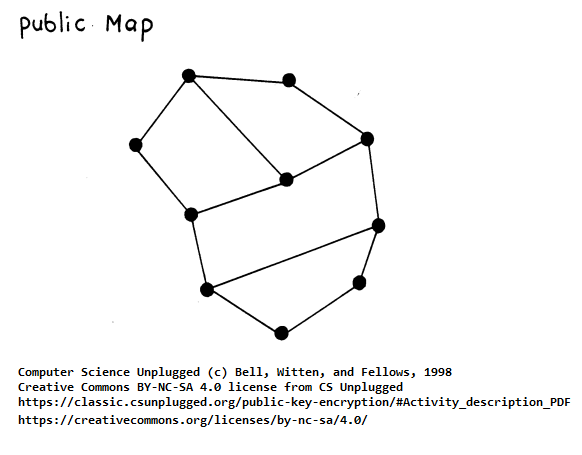

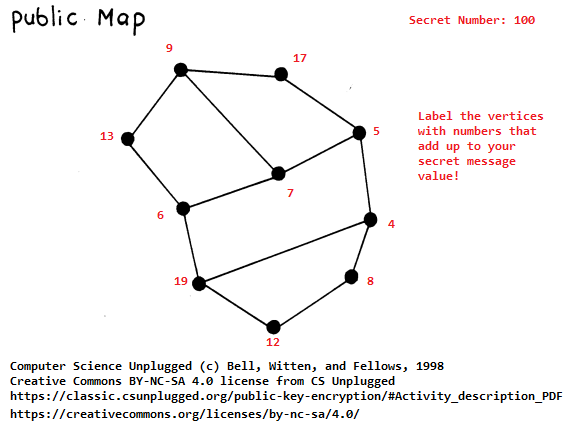

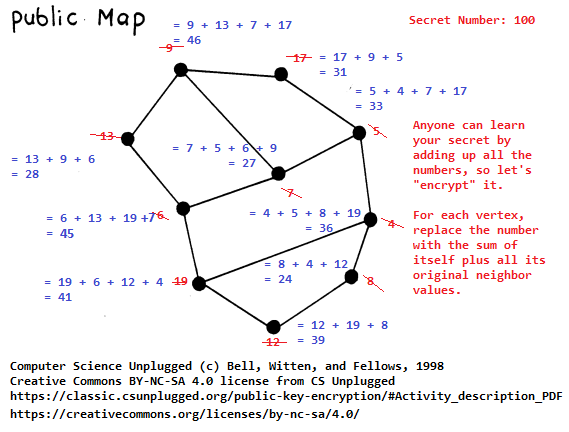

For example, we could use difficult-to-compute graph algorithms like the Vertex Cover problem as shown in this example. This is the example we’ll explore in this activity!

The public map is the key that you can use to send a secret message to someone that has the corresponding private map. The private map contains a secret about the map that allows them to decrypt the message.

To use it, first come up with a set of numbers that add up to one of your ASCII values, and put those numbers randomly on the map, labeling each vertex. This is easy to break, though, since the original value is just the sum of these numbers! Instead, take each vertex and its neighbors (there should be 4 nodes each), add up those numbers, and replace each vertex with that sum. Erase or start a new map so that the original numbers can’t be seen. Give that resulting map to another student. Can your classmate decode the message? They should not be able to. Now give it to the student with the private map (the solution to the vertex cover problem - which is difficult to compute, but gives the set of nodes that together touch all the other nodes exactly once). That student adds up only the values on the larger vertices, which is the sum of the values of each node plus the nodes they touch (which is all of them, because they’re the vertex cover nodes!), yielding the original ASCII value. Your partner can easily decode the message. This works by carefully constructing the map such that the highlighted vertices on the private map consist of the nodes that touch all vertices on the graph exactly once. This can be a difficult problem to solve if it is not provided in advance. It is breakable, though, using high school math techniques (systems of equations), in which t(i) = some partial sum of vertex values, knowing the summed values of the vertices and the neighbors on the map. Nevertheless, it is a start. We need another problem that is easy to set up but hard to break without the key.

The Knapsack Problem

A similar exercise can be accomplished with an actual cryptosystem using the Knapsack Problem. This system was devised by Whitfield Diffie, Martin Hellman, and Ralph Merkle and is known as the Merkle-Hellman Knapsack Cryptosystem. It was broken by Adi Shamir, who is the “S” (along with Ron Rivest and Leonard Adleman) in the RSA Cryptosystem! Diffie, Hellman, and Merkle also developed the Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange algorithm (although they may not have been the first to do so) for exchanging keys over an insecure channel.

Try generating a public/private key and a message using the Merkle Hellman Knapsack Cryptosystem.

Toward the RSA Cryptosystem: Using the Product of Large Prime Numbers for Public and Private Keys

William Stanley Jevons proposed in 1874 that it is very difficult to identify two numbers that, when multiplied together, would result in Jevons’s Number: 8,616,460,799. Given enough time, you might determine that the two numbers are 89,681 and 96,079 (which each happen to be prime numbers, so there are no other factors aside from Jevons’s Number itself and 1); however, you could imagine this becoming more and more difficult as the target number gets larger and larger.

We will generate a public key (that we share with the public, like our map with the number sums filled in above), and a private key (that we keep to ourselves, like the solution to the Vertex Cover problem that extracts the secret meaning from our encrypted message), using the RSA Cryptosystem. This system is based upon the product of two large prime numbers. The private key relies on the idea that it is very difficult to obtain the original prime factors from these large products.

Notice that many problems such as the map and the knapsack relied on modular arithmetic, using things that you’ve seen in school like “coprime” and “gcd.” Another difficult problem is factoring large numbers and finding large prime numbers. How did we get the modular inverse of 588 mod 881? It’s because we made sure that they were coprime to each other. Given numbers that don’t have any factors (3 and 7, 9 and 25) in common, what’s their gcd? 1 is the only number that divides them both. This means that we can find a modular inverse of the one number mod the other number, because there exists a number:

\(r^{-1}\) (in this case, \(r^{-1}\) is known as the Modular Inverse, not the traditional arithmetic inverse) such that \(rx = 1 (mod \; p)\).

Some interesting relationships in mathematics (called Fermat’s Little Theorem) show us that when two numbers are coprime, we can compute the modular inverse of their product r:

\(r^{-1} = r^{\phi(M) - 1} (mod \; M)\).

\(\phi(M)\) is known as Euler’s Totient Function, and it is simply a count of the number of integers 1 <= k < M that are coprime to m.

\(\phi(24) = 8\) (because the totatives of 24 are 1,5,7,11,13,17,19,23). So for r = 588 and q = 881, as in the Knapsack Example, we can compute the modular inverse of 588 (mod 881) as follows:

\(588^{-1} = 588^{\phi(881)-1} (mod \; 881)\).

Unfortunately, it is very difficult to compute \(\phi(M)\), and therein lies the secret! If you generate r by multiplying together two large prime numbers that you already know (this is why finding large prime numbers is an interesting problem!), you can generate a number for which it is too difficult to compute Euler’s Totient. You can very easily compute the Totient with a loop that counts all values from 2 to C, and increments a counter if the greatest common divisor of each value and C is 1. Thus, you (and probably only you) can compute the modular inverse of values mod \(M = \phi(C)\).

For now, we can look up \(\phi(881)\) on a website like http://primefan.tripod.com/TotientAnswers1000.html, but it turns out that 881 is prime, meaning that no numbers greater than 1 other than itself divide into it. This means that \(\phi(881) = (881 - 1) = 880\) (the other 880 numbers).

So \(588^{-1} = 588^{880-1} (mod \; 881) = 588^{879} (mod \; 881) = 588^{879} (mod \; 881)\). That’s \(1.917e+2434 (mod \; 881)\), or 442. See how much easier that makes the problem above to solve? Yet, it’s harder for those that don’t know the base number r and the modular inverse q, so we keep those secret. Instead, we give our partner(s) enough information to generate encrypted values to us that we can decrypt using this approach.

An Algorithm for RSA Key Generation

To generate RSA keys, first select two prime numbers A (say, 47) and B (say, 71). Normally, A and B should be very large – a small map was easy to break, after all! Multiply them together and call that \(C = AB = 47 \times 71 = 3337\).

Now compute \(\phi(C) = \phi(AB) = \phi(A)\phi(B) = (A-1)(B-1) = 46 \times 70 = 3220\), and call this number (the totient of C) M. Pick an encryption key that is coprime to \(M = 3220\). There are mathematical ways of doing this (the Extended Euclidean GCD Algorithm), but let’s just pick one since we’re using small enough numbers – how about 79. Take my word for now that it is easy to do, especially with a computer. Call this \(E = 79\).

The decryption key is the modular inverse of the encryption key \(E (mod \; 3220)\). Call this \(d = 79^{-1} = 79^{\phi(3220)-1} (mod \; 3220)\). Recall how to do this (keep in mind that 79 is coprime to M = 3220 – what a great idea, because we can use our formula!). So \(r^{-1} = r^{\phi(M) -1} (mod \; M)\) works. According to http://www25.brinkster.com/denshade/totient.html, \(\phi(M) = 1056\), but we could compute it. So now we have \(79^{-1} = 79^{1056 - 1} (mod \; 3220) = 791055 (mod \; 3220) = 1019\).

The encryption key \(C = 3337\) and \(e = 79\) make up the public key. The private key is \(d = 1019\) and \(C = 3337\). If we want to send the value 688, we compute \(688^{79} (mod \; 3337) = 1570\). To decrypt it, take \(1570^{1019} (mod \; 3337) = 688\). It actually works the other way, too. We can encrypt with the private key and decrypt with the public key. It all works because of the modular properties of relatively prime numbers. They easily “undo” each other, but it’s hard to reconstruct one number from the other.

But why would we ever want to do that? What value would we gain by being the only person who could encrypt something (with our private key) that the whole world could decrypt (with our public key)? (Click to reveal)

The information would not be private, because anyone could decrypt it. However, the public could be sure that you were the only person that could have generated that data. If we submit a document, and an exact copy of the document encrypted with our private key, the public could decrypt it and verify that it matches the non-encrypted document we sent out. This is the basis of a digital signature!The idea is that 1019 is very difficult to find even knowing \(e = 79\) and \(C = 3337\). That’s because we’d need to be able to factor 3337 into two numbers that, when one is subtracted from each and multiplied together, give 3220 – such that 79 is relatively prime to that number. If factoring was easy, we could try every number until we found it. Luckily, it isn’t so easy. Still, cryptosystems are subject to attacks similar to those you do in the newspaper, and there are some tricks (padding, salting) to dealing with that. What would you do? Some devices like RSA keys generate RSA values every minute. This is because we believe that even if these numbers can be factored, it would take more than a minute to do so, and thus the security maintained.

-

William M. Mongan. 2012. An integrated introduction to network protocols and cryptography to high school students (abstract only). In Proceedings of the 43rd ACM technical symposium on Computer Science Education (SIGCSE ’12). Association for Computing Machinery, New York, NY, USA, 664. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1145/2157136.2157364 ↩

-

William M. Mongan. 2011. Networking Applications, Protocols, and Cryptography with Java. Google CS4HS Workshop at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. ↩

-

William M. Mongan. 2012. Networking Applications, Protocols, and Cryptography with Java. Tapia Workshop at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA. ↩

-

Bell, Witten, and Fellows. 1998. Computer Science Unplugged - Public Key Encryption. Available at https://classic.csunplugged.org/public-key-encryption/ ↩

-

Jeffrey L. Popyack. RSA Calculator. https://www.cs.drexel.edu/~jpopyack/Courses/CSP/Fa17/notes/10.1_Cryptography/RSAWorksheetv4e.html ↩